|

Thank you for this opportunity to interact with eminent business leaders of India and distinguished members of the FICCI. I wish to thank the organisers for hosting this event, undeterred by this still unfolding pandemic that, on a daily basis, tests our resilience and capacity to save lives, households, businesses and the economy.

2. The end-August press release of the National Statistics Office (NSO) was a telling reflection of the ravages of COVID-19. Nevertheless, high frequency indicators of agricultural activity, the purchasing managing index (PMI) for manufacturing and private estimates for unemployment point to some stabilisation of economic activity in Q2, while contractions in several sectors are also easing. The recovery is, however, not yet fully entrenched and moreover, in some sectors, upticks in June and July appear to be levelling off. By all indications, the recovery is likely to be gradual as efforts towards reopening of the economy are confronted with rising infections.

3. The global economy is estimated to have suffered the sharpest contraction in living memory in April-June 2020 on a seasonally adjusted quarter-on-quarter basis. World merchandise trade is estimated to have registered a steep year-on-year decline of more than 18 per cent in Q2 of 2020, according to the Goods Trade Barometer of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). High frequency indicators point to a trough in global economic activity in April-June quarter and a subsequent recovery is underway in several economies, such as the USA, UK, Euro-area and Russia. The global manufacturing and services PMIs rose to 51.8 and 51.9, respectively, in August from 50.6 for both in July. Yet, infections remain stubbornly high in the Americas and are increasing again in many European and Asian countries, causing some of them to renew containment measures.

4. On the back of large policy stimulus and indications of the hesitant economic recovery, global financial markets have turned upbeat. Equity markets in both advanced and emerging market economies have bounced back, scaling new peaks after the ‘COVID crash’ in February-March. Bond yields have hardened in advanced economies on improvement in risk appetite, fuelling shift in investor’s preferences towards riskier assets. Portfolio flows to EMEs have resumed, and this has pushed up EME currencies, aided also by the US dollar’s weakness following the Fed’s recent communication on pursuing an average inflation target. Gold prices moderated after reaching an all-time high in the first week of August 2020 on prospects of economic recovery.

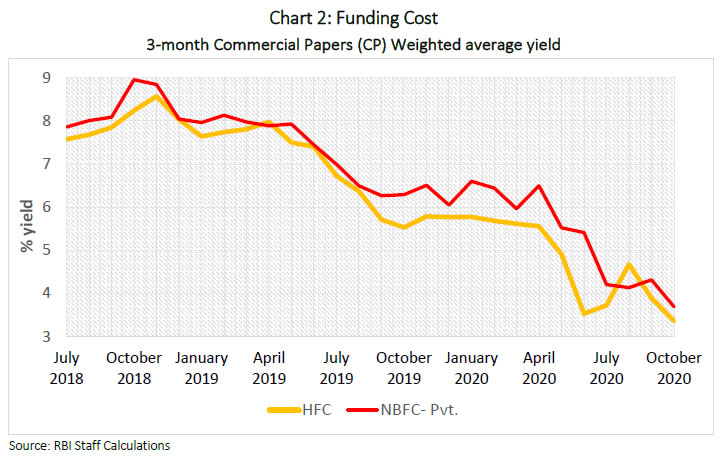

5. Financial market conditions in India have eased significantly across segments in response to the frontloaded cuts in the policy repo rate and large system-wide as well as targeted infusion of liquidity by the RBI. Despite substantial increase in the borrowing programme of the Government, persistently large surplus liquidity conditions have ensured non-disruptive mobilisation of resources at the lowest borrowing costs in a decade. In August 2020, the yield on 10-year G-sec benchmark surged by 35 basis points amidst concerns over inflation and further increase in supply of government papers. Following the RBI’s announcement of special open market operations (OMOs) and other measures to restore orderly functioning of the G-sec market, bond yields have softened and traded in a narrow range in September. Although bank credit growth remains muted, scheduled commercial banks’ investments in commercial paper, bonds, debentures and shares of corporate bodies in this year so far (up to August 28) increased by ₹5,615 crore as against a decline of ₹32,245 crore during the same period of last year. Moreover, the benign financing conditions and the substantial narrowing of spreads have spurred a record issuance of corporate bonds of close to ₹3.2 lakh crore during 2020-21 up to August.

6. The immediate policy response to COVID in India has been to prioritize stabilization of the economy and support a quick recovery. Polices for durable and sustainable high growth in the medium-run after the crisis, nevertheless, are equally important, and in my address today I propose to dwell upon that issue squarely – what could potentially lift up the Indian economy to trend growth as the recovery begins?

7. While interacting with members of the National Council of the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) on July 27, 2020, I had covered five major dynamic shifts taking place in the economy: (i) fortunes shifting in favour of the farm sector; (ii) changing energy mix in favour of renewables; (iii) leveraging information and communication technology (ICT) and start-ups to power growth; (iv) shifts in supply/value chains, both domestic and global; and (v) infrastructure as the force multiplier of growth. Today, I would like to touch upon five areas that, I feel , would determine our ability to step up and sustain India’s growth in the medium-run: (i) human capital, in particular education and health; (ii) productivity; (iii) exports, which is linked to raising India’s role in the global value chain; (iv) tourism; and (v) food processing and associated productivity gains.

(i) Human Capital: The Importance of Education and Health

8. Investing in people adds to the stock of skills, expertise and knowledge available in a country, and that is critical to maximise its future growth potential. The assignment of importance to education dates back to Plato, Aristotle, Socrates and Kautilya. Its significance for economic development has received progressively increasing attention in recent decades, especially in the work of several Nobel laureates, including T.W. Schultz, Gary Becker, Robert Lucas and James Heckman. There has come about an explicit recognition of education as human capital in endogenous growth theory, backed up by cross-country empirical evidence.

9. In India, states with higher literacy rates are found to have higher per capita income, lesser infant mortality, better health conditions and also lower poverty. Education and skill development, however, contribute less than half a percentage point to our overall labour productivity growth. In order to reap the demographic dividend, we have to raise expenditure on education and acquisition of skills substantially. It is important to recognise that investment in education pays by raising average wages. In its Global Education Monitoring Report 2012, the UNESCO highlighted that every US$1 spent on education generates additional income of about US$10 to US$15. A World Bank (2014) study showed that an additional year of schooling increases earnings by 10 per cent a year. Higher education also contributes to economic development through greater sensitivity to environment/climate change, energy use, civic participation and healthy lifestyle.

10. The New Education Policy 2020 (NEP), a historic and much needed new age reform, has the potential to leverage India’s favourable demographics by prioritising human capital. The goal to increase public investment in the education sector to 6 per cent of GDP must be pursued vigorously. Public-private partnerships (PPPs) can develop necessary infrastructure, without jeopardising financial viability of private investment while ensuring quality education at affordable costs. Indian banks and the financial system would need to respond proactively to opportunities arising from the NEP for new financing.

11. Besides improving access to education, focus on quality of education and research will be critical to shape the outcome of education on economic development. Skill acquisition is more important than mere mean years of schooling. The assessment of quality aspect of education often requires a multi-dimensional approach: reading and language proficiency; mathematics and numeracy proficiency; and scientific knowledge and understanding1. The emphasis on quality of education must begin at the foundation stage in schools up to plus 2 level. At another level, the formation of the National Research Foundation as announced in the NEP is a welcome step to fund outstanding peer-reviewed research and to actively promote research in universities and colleges. The creation of a National Educational Technology Forum as a platform for use of technology in education is a necessary step to meet the requirement of rapidly changing labour market.

12. Health is another vital component of human capital. Good health increases life expectancy and productive working years. In high income countries, per capita health expenditure in 2017 was about US$ 2937, as against US$ 130 in low middle-income countries (which include India). Initiatives such as the Pradhan Mantri Bharatiya Jan Aushadi Pariyojana (PMBJP) and Pradhan Mantri National Dialysis Programme (PMNDP), free drugs and diagnostic service provision initiatives are expected to improve the quality and affordability of healthcare. The most important step towards providing affordable healthcare has been the launch of the Ayushman Bharat Yojna, which lays down the foundation of a 21st century health care system, covering both government and private sector hospitals.

13. COVID has brought to the fore the importance of easy access to health services to contain the mortality rate, given significant inter-state and intra-state differences in healthcare infrastructure. While laudable crisis time response to scale up health infrastructure has helped in dealing with the health emergency, a more comprehensive approach similar to NEP for the health sector may be warranted, which must also cover deeper penetration of insurance, given the high burden of out of pocket expenses in India, and also preventive care. Greater attention is required to improve the health ecosystem by ensuring creation of new medical colleges, higher number of PG seats and colleges for paramedics and nursing.

(ii) Productivity growth

14. By any reckoning, COVID-19 will leave long lasting scars on productivity levels of countries around the world. According to a recent World Bank assessment2, COVID-19 could entail adverse effects on productivity because of dislocation of labour, disruption of value chains and decline in innovations. During earlier episodes of epidemics in the past – Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), Ebola and Zika – productivity is estimated to have declined by about 4 per cent over three years. The COVID impact on productivity could be expected to be much larger.

15. KLEMS (capital; labour; energy; materials; and services), a database hosted by the RBI, shows that the Indian economy experienced an overall productivity growth of 0.9 per cent per annum, on an average, over the period 1980-81 to 2017-18. In the immediate post-GFC period – from 2008-09 to 2012-13 – there was a decline in productivity by 0.3 per cent annually, while the period thereafter upto 2017-18 recorded annual productivity growth of 2.4 per cent. The contribution of productivity growth to the overall GDP growth of the Indian economy over the period 1980-81 to 2017-18 was about 15 per cent. During 2013-14 to 2017-18, its contribution increased significantly to about 34 per cent.

16. The share of patents applied and granted to India in total patents granted globally has been rising in recent years. India’s share, however, continues to be low at less than 1 per cent. Globally, the private sector plays a major role in R&D expenditure, while in India, a major part of R&D expenditure is incurred by the government, particularly on atomic energy, space research, earth sciences and biotechnology. Stepping up R&D investment in other areas would require more efforts by the private sector, with the government focusing on creating an enabling environment.

17. With a view to further promoting innovations in financial services, the Reserve Bank has announced an Innovation Hub with a focus on new capabilities in financial products and services that can help deepening financial inclusion and efficient banking services. Ongoing efforts are yielding results. India has recently entered the group of top 50 countries in the global innovation index (GII) list of 2020 for the first time. The India Innovation Index, released by Niti Aayog last year, has been widely accepted as a major step in the direction of decentralisation of innovation across all states of the country. Sustaining this process will be vital, given particularly the trend decline in saving and investment rate in India.

(iii) Exports and Global Value Chains (GVCs)

18. In the post global financial crisis (GFC) period, a view has emerged that the era of export-led growth is over, and India missed the opportunity by not prioritizing exports at the right time. Globally, the key impediments to exports post-GFC include: (a) generalized increase in protectionism by trading partners; (b) weak global demand conditions; (c) race to the bottom (to gain unfair competitive advantage, by using a policy mix of competitive depreciation, subsidies, tax and regulatory concessions); and (d) automation, reducing the cost advantages stemming from cheap labour.

19. Notwithstanding these impediments, and also the significant decline in trade intensity of world GDP growth in the post-GFC period, opportunities for expanding exports arise from the vastly altered global landscape for trade where more than two thirds of world trade occurs through global value chains (GVCs)3. The higher the GVC participation of a country, the greater are the gains from trade as it allows participating countries to benefit from the comparative advantage of others participating in the GVC. Services such as transportation, banking, insurance, IT and legal services, branding, marketing and after sale services are integral to GVCs.

20. India’s participation in GVCs has been lower than many emerging and developing economies. India has global presence in low GVC products such as gems and jewellery, rice, meat and shrimps, apparels, cotton, and drugs and pharmaceuticals.

21. Among the sunrise sectors that offer potential for higher exports in the post-COVID period are drugs and pharmaceuticals where India enjoys certain competitive advantages. With strong drug manufacturing expertise at low cost, India is one of the largest suppliers of generic drugs and vaccines. Some Indian manufacturers have already entered into new partnerships with global pharma companies to produce vaccines on a large scale for both domestic and global distribution. The Government has also approved an investment package for promotion of bulk drug parks and a production-linked incentive scheme is in place to enhance domestic production of drug intermediates and active pharmaceutical ingredients. A sharp policy focus on other GVC intensive “network products”, including equipment for IT hardware, electrical appliances, electronics and telecommunications, and automobiles would also provide the cutting edge to India’s export strategy with considerable scope for higher value additions.

22. Domestic policies need to focus on the right mix of local and foreign content in exports while aiming to enhance participation in GVCs. Firms that engage in both imports and exports are found to be far more productive than non-trading firms (World Bank, 2020)4. While choosing trade partners through free trade agreements (FTAs), it is also important to learn from global experience and nurture those trade agreements that go beyond traditional market access issues. Provisions relating to investment, competition, and intellectual property rights protection have a larger positive impact on GVC trade and need to be assiduously cultivated and ingrained into India’s export ecosystem.

(iv) Tourism as an Engine of Growth

23. Tourism has been one of the sectors in the economy most severely impacted by COVID-19. At the same time, this is also a sector where pent up demand could drive a V shaped recovery when the situation normalises.

24. India has immense potential to meet a diverse range of tourist interests – religion; adventure; medical treatment; wellness and yoga; sports; film making; and eco-tourism. We have four major biodiversity hotspots, 38 UNESCO World heritage sites5, 18 biosphere reserves, over 7,000 km of coastline, rain forests, deserts, tribal habitation and a multi-cultural population. The challenge nevertheless is to scale up our tourism market and enhance its contribution to economic development.

25. As per the Third Report of Tourism Satellite Account for India (TSAI) 2018, the share of tourism in GDP was 5.1 per cent in 2016-17 and the share in employment was 12.2 per cent (with the direct and indirect shares at 5.32 per cent and 6.88 per cent, respectively). In 2018-19, tourism’s share in employment increased further to 12.8 per cent, with the total size of employment at 87.5 million. The employment elasticity in this sector, thus, appears to be high. India attracted 10.89 million foreign tourists in 2019, an increase of 3.2 per cent over the previous year. The foreign exchange earnings generated by the sector during the same period was about ₹2 trillion, a year-on-year increase of more than 8 per cent. The country also jumped six positions to 34 out of 140 counties in the Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index 2019 of the World Economic Forum (WEF).

26. Recognising the potential of the sector, the Government has provided targeted policy support. The Ministry of Tourism has two major schemes: Swadesh Darshan for Integrated Development of Theme-Based Tourist Circuits; and PRASHAD as a Pilgrimage Rejuvenation and Spiritual, Heritage Augmentation Drive for development of tourism infrastructure in the country, including historical places and heritage cities.

27. The multi-pronged supportive policy interventions in the sector may have to be reviewed and revamped, if tourism has to contribute more to the economy matching its potential. A closer look at some of the global leaders in travel and tourism such as France and Spain would suggest that these countries not only have excellent natural and cultural resources, but policies to support an exceptionally attractive tourist infrastructure, including a high hotel density offering all range of choices, quality public transport systems, networked air connectivity with considerable route capacity, and most importantly, safety and security.

28. Initiatives need to be taken in the direction of improving and integrating various modes of transportation (linking air/train/metro/road/sea) with the provision for single point of booking, e-registration of service providers (travel agents, transport operators, hotels, tourist guides, etc.). Strict provisions of penalty for non-compliance would boost confidence of tourists, alongside an effective and speedy grievance redressal system for both domestic and foreign tourists. Research conducted by a private agency6 suggested that if we can increase international tourist arrivals to 20 million (i.e., about double of current arrivals), the incremental income would be US$19.9 billion, benefiting an additional 1 million people in the travel and tourism industry.7

(v) Food Processing for Surplus Management

29. COVID has brought the importance of food security and food distribution or supply chain network to the forefront of public policy debate in India. Successive years of record production of foodgrains and horticulture crops has transformed India into a food surplus economy. Recognising this challenge, much of the policy attention in recent years for the sector has focused on addressing post-production frictions, comprising agri-logistics, storage facilities, processing and marketing. Greater focus on processed food is one option that could help in dealing with multi-pronged challenges of surplus management. Development of the food processing industry is likely to benefit the farm sector and the economy through greater value addition to farm output, reducing food wastages, stabilising food prices, expanding export opportunities, encouraging crop diversification, providing direct and indirect employment opportunities, increasing farmers’ income and enhancing consumer choices.

30. Food processing is a sunrise industry. Globally, its importance in the consumer basket has increased over time, led by rising per capita incomes, urbanisation, and change in consumer perceptions regarding quality and safety. Despite having huge growth potential, the food processing industry in India is currently at a nascent stage, accounting for less than 10 per cent of total food produced in the country. As a result, despite being one of the largest producers of several agricultural commodities in the world, India ranks fairly low in the global food processing value chain.

31. There is a need to move up the value chain. Moreover, the food processing industry in India is largely domestically oriented, with exports accounting for only 12 per cent of total output. India can move up in the global agricultural value chain by increasing its share of processed food exports, for which quality standards will be a critical factor.

32. Food processing also offers huge employment potential. In India, while the food processing industry’s contribution to overall Gross Value Added (GVA) is only 1.6 per cent, it accounts for 1.8 million (12.4 per cent) and 5.1 million (14.2 per cent) jobs in registered and un-incorporated sectors, respectively. Recognising this, the government has set the target for raising the share of processed food to 25 per cent of the total agricultural produce by 2025. The food processing sector was also opened up for 100 per cent FDI in 2016 under the automatic route. Further, in 2017, 100 per cent FDI under the government route for retail trading, including through e-commerce, was permitted in respect of food products manufactured and/or produced in India. For ensuring adequate credit flows, the Reserve Bank has accorded priority sector status to the food processing industry in 2015.

Conclusion

33. In my address today, I have highlighted five critical areas that can determine the shape of our post-COVID trend growth. While dealing with the immediate crisis management challenges, we need to strategically prepare for our combined overriding goal – the pursuit of strong and sustainable growth. The private business sector has a critical role in each of the five areas I covered today. The enabling policy environment would evolve around the initiatives taken by India’s businesses to seize these opportunities and actualise the potential of the Indian economy as a rising economic power of the 21st century. COVID-19 has changed our lives and it is increasingly clear that life will never be the same again. We should look upon these fundamental changes as opportunities rather than threats, converting them into game changing new vistas of progress. I do believe that together as a nation, we can certainly do it. Let me conclude on this optimistic note.

|